Large earthquakes present a significant risk globally and addressing earthquake risk—both from the standpoint of life safety and damage/economic impact—is a significant societal challenge for virtually every element of the built environment, including energy, transportation, health, data/commerce, and urban infrastructure. The U.S. Department of Energy, in support of the safety of DOE mission-critical facilities, has long been at the forefront of building advanced capabilities for seismic hazard and risk assessment, and these capabilities can extend to broad societal benefit and impact. Earthquake Simulation (EQSIM) is tapping the tremendous developments that are occurring in high-performance computing (HPC) to advance the understanding of the physics of earthquake processes, data collection, and data exploitation to help advance earthquake hazard and risk assessments. EQSIM application codes are removing the reliance on traditional simplifying idealizations, approximations, and sparse empirical data. Instead, the focus is on resolving the fundamental physics uncertainties in earthquake processes. Through EQSIM, regional-scale ground motion simulations are becoming computationally feasible, and simulation models that rigorously connect the domains of seismology and geotechnical and structural engineering are becoming accessible. This simulation-based approach to evaluating earthquake risk is opening an entirely new avenue for the deeper understanding of earthquake phenomenon; allowing for the very detailed, virtual exploration of significant earthquakes; and ultimately providing an important practical tool for earthquake risk quantification.

Project Details

The EQSIM application development project is focused on creating an unprecedented computational tool set and workflow for earthquake hazard and risk assessment. Starting with a set of existing codes—SW4 (a fourth-order, 3D seismic wave propagation model), NEVADA (a nonlinear, finite displacement program for building earthquake response), and OPENSEES (a nonlinear finite-element program for coupled soil-structure interaction)—EQSIM is creating an end-to-end capability to simulate from the initiation of fault rupture to surface ground motions (i.e., earthquake hazard) and ultimately to infrastructure response (i.e., earthquake risk). EQSIM’s ultimate goal is to remove computational limitations as a barrier to scientific exploration, understanding earthquake phenomenology, and practical earthquake hazard and risk assessments.

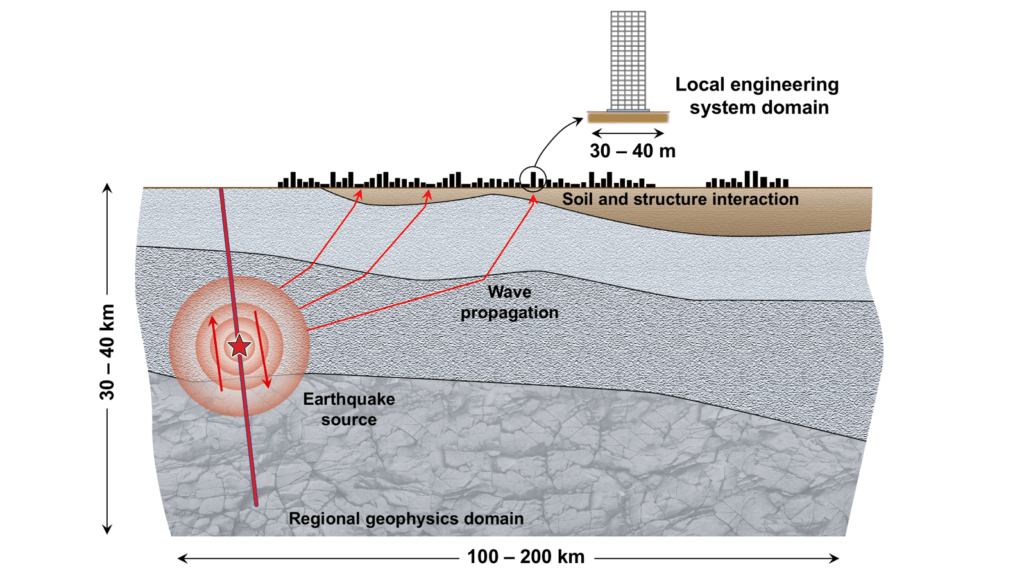

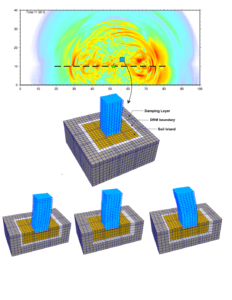

Traditional earthquake hazard and risk assessments for critical facilities have relied on empirically based approaches that use historical earthquake ground motions from many different locations to estimate future earthquake ground motions at a specific site of interest. Because ground motions for a particular site are strongly influenced by the physics of the specific earthquake processes—including the fault rupture mechanics, seismic wave propagation through a heterogeneous medium, and site response at the location of a particular facility—earthquake ground motions are very complex with significant spatial variation in frequency content and amplitude. The homogenization of many disparate records in traditional empirically based ground motion estimates cannot fully capture the complex site specificity of ground motion. Over the past decade, interest in using advanced simulations to characterize earthquake ground motions (i.e., earthquake hazard) and infrastructure response (i.e., earthquake risk) has accelerated significantly. However, the extreme computational demands required to execute hazard and risk simulations at a regional scale have been prohibitive. One fundamental objective of the EQSIM application development project is to advance regional-scale ground motion simulation capabilities from the historical computationally limited frequency range of ~0–2 Hz to the frequency range of interest for a breadth of engineered infrastructure of ~0–10 Hz. Another fundamental objective of this project is to implement an HPC framework and workflow that directly couple earthquake hazard and risk assessments through an end-to-end simulation framework that extends from earthquake rupture to structural response, thereby capturing the complexities of interaction between incident seismic waves and infrastructure systems (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The multiscale computational challenge of fault-to-structure simulations starting from the earthquake source, continuing through regional-scale wave propagation in a heterogeneous earth at a scale of hundreds of kilometers (“Regional geophysics domain”), and ending at local interaction between complex incident seismic waves with a soil-structure system at a scale of 30–50 m (“Local engineering system domain”).

To achieve the overall goals, two fundamental challenges must be addressed. First, regional-scale forward ground motion simulations must be effectively executed at an unprecedented frequency resolution with much larger, much faster models. Achieving fast earthquake simulations is essential for allowing the parametric variations needed to span critical problem parameters (e.g., multiple fault rupture scenarios). Second, as the ability to compute at higher frequencies progresses, there will be a need for better characterization of subsurface geologic structures at finer and finer scales; thus, a companion schema for representing fine-scale geologic heterogeneities in massive computational models must be developed.

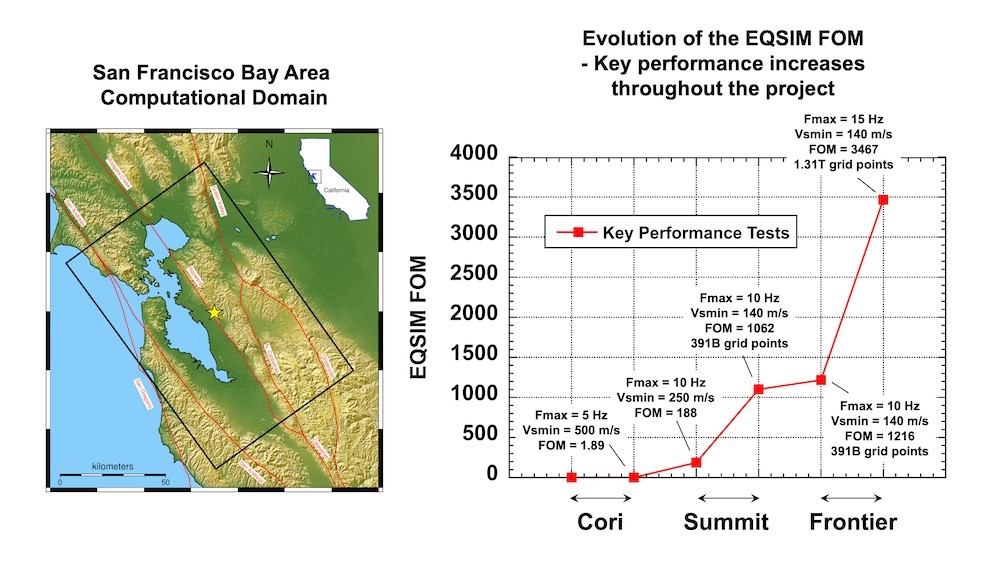

To evaluate regional-scale simulations and measure the computational progress of the application development and exascale performance goals of this project, a representative large regional-scale detailed model of the San Francisco Bay Area (SFBA) was created (Figure 2). This model includes all the necessary geophysics modeling features (e.g., 3D geology, earth surface topography, material attenuation, nonreflecting boundaries, fault rupture models). For a 10 Hz simulation, the computational domain includes up to 300 billion grid points in the finite difference domain for models that contain fine-scale representations of soft near-surface sedimentary soils. The SFBA model provides a comprehensive basis for testing and evaluating advanced physics algorithms and computational implementations.

Figure 2. The computational model of the SFBA and snapshots of seismic waves emanating from a Hayward fault earthquake simulation at 6.3 seconds, 13.2 seconds, 20.1 seconds, 24.9 seconds, 29.9 seconds, and 34.9 seconds.

Figure 3. Coupling of a regional geophysics model (top) with a local soil-structure model via a DRM boundary (middle) and time snapshots of soil island-building response (bottom).

Figure of Merit (FOM)

Figure of Merit (FOM) is a quantitative metric of the scientific work rate of an application. As the code is optimized to run faster and more capable compute platforms become available, the FOM increases. Increasing the FOM is actually an enabler of more science. Running bigger problems faster provides for more realistic simulations because of the higher-fidelity resolution of earthquake ground motions important to infrastructure systems. An increased FOM means major science advancement.

Significant progress was achieved in EQSIM performance that corresponds to significant increases in the EQSIM FOM from SFBA performance runs, as shown in Figure 4. This advancement reflects the integrated contributions of advanced algorithm implementation, the development of fast and reliable massive I/O, and the effective utilization of emerging GPU-based computers. Starting with the first SFBA regional runs on the Cori computer at Lawrence Berkley National Laboratory at the inception of the EQSIM project to the most recent performance testing on the Frontier platform at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, the EQSIM FOM has increased by a factor of 3467 as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Advancements in EQSIM FOM: Benchmark performance tests.

| Benchmark simulation platform | Code attributes | Frequency resolution (Hz) | Minimum shear wave speed (m/s) | Number of compute nodes | Wall clock time (hours) | FOM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cori | Initial run of EQSIM SW4 ported to Cori | 3.67 | 500 | 2048 | 23.9 | 1.0 |

| Cori | EQSIM with optimized hybrid message passing interface/OpenMP loops | 4.17 | 500 | 8192 | 8.9 | 1.89 |

| Summit | EQSIM including enhanced I/O optimized mesh refinement | 10.0 | 250 | 922 | 23.7 | 188 |

| Summit | Utilization of a large portion of Summit and resolution of soft near-surface soils (Vsmin 140 m/s) | 10.0 | 140 | 3,600 | 42.7 | 1062 |

| Frontier | First EQSIM large runs on Frontier | 10.0 | 140 | 3072 | 37.5 | 1209 |

| Frontier | Largest completed run for the Hayward fault | 15.0 | 140 | 5088 | 66.2 | 3467 |